I’ve neglected this blog for too long, fear not though, I am currently putting together some ideas which will enliven it, hopefully. In the meantime, here’s something I’ve done recently on Saturday Night and Sunday Morning.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Reflecting on the legacy of the BBC’s ‘Play for Today’ series, Hanif Kureishi noted: ‘On my way up to London the morning after a Play For Today I’d sit in the train listening to people discussing the previous night’s drama and interrupt them with my own opinions.’ I’ve always loved this quote because it gave me a window into an apparently bygone age where the broad address of television stimulated debate across the country.

Today, the day after BNP leader Nick Griffin’s appearance on the BBC 1’s Question Time, I’ve finally got a glimpse of what Kureishi was talking about. Everyone I’ve spoken to has had an opinion on the show, and I keep hearing snatches of arguments and debates everywhere I go. This is what happens when the political process galvanises a significant section of the populace through the mass media. TV dramatists and producers, take note.

Right, my thesis is being bound as I speak, so it seems like a perfect time to get back to some regular blogging.

Top tens are probably quite reductive, a bit cheap and hugely contrived, but they’re also fun. To get things rolling again I thought I’d start off with a series of top tens, they are, by no means, definitive or an attempt by me to say these films are the ‘best of the best’, the criteria is simple and selfish; I have to like them, a lot.

So as my ‘specialist area’ is British cinema, I’m starting with Words on What I’ve Seen’s Top Ten British Films:

10. Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (dir. Stephen Frears, 1987)

My Beautiful Laundrette is widely regarded as one of the definitive films of the 1980s, it made a star of Daniel Day-Lewis, and was Film on Four’s first major success. Stephen Frears and Hanif Kureishi’s 1987 follow-up Sammy and Rosie Get Laid was largely derided on its release as a bloated, pretentious flop. But it’s time for some serious revision. As far as I can tell the film is unavailable everywhere (DVD distributors, get your act together), which is a massive shame, as, for me, it’s a real flawed masterpiece.

Kureishi’s emblematic, agit-prop style is given full rein in a film which balances the 1980s British cinema’s often opposing impulses of realism and modernist experimentation. Sexual freedom, post-colonialism, Thatcherite authoritarianism, nationhood, the city, race-relations and class all come under the microscope in a film which, admittedly, tries to say an awful lot in its 100 minutes. But this ambition is deserving of our attention and re-appraisal. There are times when the film distils its wide thematic reach into some wonderfully concise moments of poeticism, witness, for example, the moment when ‘I Vow to Thee My Country’ plays against fraught images of travellers being forced off a waste land by brutish property developers; a scene which stirs up British cinema’s long-held concern with the disjunctions between national mythology and social reality.

9. Bleak Moments (dir. Mike Leigh, 1971)

I could have chosen any number of Leigh films, personally I’m a big fan of his TV work, so expect an inclusion or two in my upcoming ‘single drama’ top ten. As far as his films go, 2002’s All or Nothing is hugely underrated, as is the wonderful Life is Sweet (1990), which is far superior to the more celebrated High Hopes (1988). But it’s Bleak Moments, Leigh’s most subtle and minimal film, which fascinates me the most. A document of a socially awkward and repressed typist and her mentally disabled sister, Bleak Moments is a meditation on silence and stillness when so many of the director’s other works draw their richness from dense dialogue and bodily quirks. Seek it out.

8. Sunday Bloody Sunday (dir. John Schlesinger, 1971)

Released in the wake of the Oscar winning Midnight Cowboy, this intensely personal and scaled-back (in comparison with the rest of Schlesinger’s oeuvre) portrait of bohemian 70s London is a real joy. The film is built around Daniel (Peter Finch) a Jewish doctor, and Alex (Glenda Jackson), a recruitment executive, and their ‘sharing’ of the enigmatic bisexual artist, Bob (Murray Head). The film’s complexity is drawn not only from its canny dissection of the sexual mores of its characters, but the constant mumblings of a nation in decline (muffled radio news, a queue of junkies at an all-night pharmacy), which compound a sense of one social-class in complete separation from another. Finch’s performance is also a real joy, reaching its climax in a final monologue delivered to camera.

7. Somers Town (dir. Shane Meadows, 2008)

Like with Leigh, I could have picked most Meadows films in this top ten. But Somers Town, arguably his most low-key theatrical release, sees all of the director’s virtues distilled beautifully. Quite simply the finest director working in Britain today, Meadows combines a sympathetic but always poetic aesthetic, with an organic approach to dialogue and narrative, which should ensure that in years to come he will be recognised as a true force in British culture.

6. It Always Rains on Sunday (dir. Robert Hamer, 1947)

Before the New Wave, Ken Loach and Mike Leigh, the embryo of social realist cinema was hatched by Ealing’s Robert Hamer, in this stunningly atmospheric slice of post-war Britain. This ambiguous portrait of morally bereft and sexually repressed working-class London, eschews the paternalistic lectures that would come to define British cinema’s post-war engagement with realism; the social problem film of the ‘50s.

Taking a crumbling domestic environment as its starting point, the film explores a series of characters across its Bethnal Green setting. Never slipping into one-dimensional caricature or stereotype, its greatest strength is a rejection of the idealised nation-as-family motif which underpinned much of Ealing’s output. Prolific character actor John Slater’s villainous, Lou Hyams is worth the price of the DVD alone.

5. Millions Like Us (dirs. Frank Launder and Sydney Gilliat, 1943)

The propagandist cinema of wartime, which combined pre-existing melodramatic devices with the hitherto underused documentary aesthetic of the documentary movement, offered up many classic British films. Launder’s and Gilliat’s tale of women working in a munitions factory, is my personal choice. One of my all-time favourite British actors, Eric Portman, is superb as Charlie Forbes, the no-nonsense factory foreman who falls for the upper-middle class, Jennifer (Anne Crawford).

Class and gender in wartime are given a public service sheen, but what distinguishes the film ahead of its contemporaries is the manner it borrows the formal components of the British documentary tradition and integrates them seamlessly.

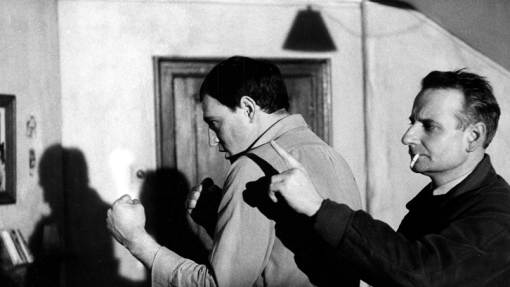

4. Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (dir. Karel Reisz, 1960)

The film that changed British cinema forever, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, should be in any top ten for its influence alone. Releasing the realist address from the shackles of the aforementioned ‘social problem’ film and opening up the staid British cinema to a wealth of European and world cinema influences, Reisz and his fellow New Wave practitioners, married stylistic verve with a commitment to hitherto suppressed areas of working-class life. Albert Finney’s Arthur Seaton was a seismic force in destroying the myth of a silent and deferential under-class.

3. A Canterbury Tale (Powell and Pressburger, 1944)

While the rest of the British film industry was contributing to the war effort with stirring realist portraits of Britain as the sum of its parts, Powell and Pressburger saw the war as an opportunity to solidify their idiosyncratic and romantic exploration of British mythology. This updated Chaucerian narrative is a stunning poem on the sublime and spiritual heart of the nation. A ‘what we are fighting for’ document, which evokes an idealised Britain beyond its surface, A Canterbury Tale is a true classic.

2. Listen To Britain (dir. Humphrey Jennings, 1942)

My favourite of Jennings’ symphonies on social interconnection, Listen to Britain is a stunning collage of image and sound which attempts to portray a defiant nation across its many diverse but equally worthy parts. For me, the film now looks like an elegiac love letter for an idealistic social democratic vision. Wonderful and heartbreaking.

1. This Sporting Life (dir. Lindsay Anderson, 1963)

One of the most artistically ambitious films of the post-war period, Anderson’s This Sporting Life is also the most complete examination of working-class masculinity and repressed emotion that I have ever seen.

A pervasive atmosphere of fatalism creeps at the edges of every frame, due in large part to Roberto Gerard’s score and Anderson’s expansive treatment of external space in convergence with a narrow and cramped interior mise-en-scene construction. Rachel Roberts gives a truly superb performance as Margaret, the embittered widow and the object of Frank’s (Richard Harris) impossible love, but it is the physicality of Harris who dominates. Fascinatingly, Anderson’s unspoken longing for his star (a relationship characterised in the Paul Sutton edited Lindsay Anderson: The Diaries) seems to be alive in the underlying and never resolved tension between camera and protagonist.

Sorry for the recent lack of activity on here, normal service will be resumed shortly. A combination of impending thesis submission and moving house have left little room for blogging.

What a week this has been for British TV drama, Monday saw the return of The Street and last night BBC2 gave us Freefall, Dominic Savage’s uncompromising account of the financial crisis. Following on from BBC1’s recent Occupation, Freefall can be seen to reflect the gentle flowerings of the revival of relevant and conscious television drama at the Beeb.

The most immediate strength of Freefall is the manner in which Savage emblematises the onset of the crisis within three identifiable characters from across the social spectrum, in doing so he renders an abstract economic idea in human terms, across the class system. The characterisation is three-fold: firstly there is Gus (Aidan Gellen), a high-flying banker who gorges himself on the mortgage markets, seemingly intoxicated by greed. Slightly further down the economic food chain is Dave (Dominic Cooper) a hugely successful and unscrupulous mortgage broker who misleads an old school friend into taking out a mortgage he could never afford. Said friend, Jim (Joseph Mawle), is a hardworking security guard and father of two, frustrated by his family’s limited existence on a council estate he needs little encouragement to ‘move up’ into home ownership. All three characters enjoy the fruits of the boom in the first half of the film and quickly realise the party is over in the second, with Savage bringing the action forward to 2008.

While this structure may seem overly rigid, and even contrived in its three-way representation of the financial crisis’ protagonists and antagonists, Savage makes the characterisation work by underpinning it with bold formal and aesthetic motifs. In the most immediate sense, the dialogue is – partly at least – improvised. Actors occasionally stumble over the lines, just as we all do in everyday exchanges; the veracity of conversation and the authentic rhythm of dialogue is acutely observed and delivered here with consummate craft by Freefall’s highly impressive players. This aural and dialogical realism is reflected in Savage’s handheld camera; which is sometimes intensely close to its subjects – suggesting invasiveness or empathy depending on the situation – and sometimes distanced; observing characters unobtrusively or simply reflecting on their solitude. Savage is also fond of the jump-cut, deploying it repeatedly as a barrier to identification or at times reversing this intention and using it like a more formalised and conventional close-up, I’m thinking particularly of the moment in which Jim’s wife Mandy (Anna Maxwell-Martin) is told of the couple’s spiralling mortgage debts: the initial medium-shot of her on the phone suddenly jumps to a close-up as she realises the depths of their predicament. This almost coarse aesthetic register is contrasted with the manner in which Savage frames external environments, displaying an Antonioni-like affection for vast and static man-made spaces: think of the moment when a depressed Jim stares up to the skies in an isolated car park, or when Gus and Gary (Riz Ahmed) stand outside their offices as the markets begin to freeze.

Savage’s eclectic textual palate fosters a tone and an atmosphere in which the aforementioned narrative structure is never over-bearing or didactic. The pursuit of naturalism converges with a cinematic concern for space and environment while the ‘issues’ that the film engages with are persistently at its core. This is a story of today; a drama-documentary which is cinematic in its scope and televisual in its content.

Freefall is an example of British art about Britain, for British people. This is exactly what the BBC should be doing.

David Forrest

First up, many apologies for my recent neglect of this blog. I’ve been working on an article for the past couple of the weeks, so doing a film and tv blog at the same time feels a bit like a busman’s holiday. I hope this compensates a little:

Jimmy McGovern’s The Street returns to UK screens on Monday night and I can’t wait.

In my post on The Wire, I suggested that the only UK drama that came close to the Baltimore saga was McGovern’s intricate masterpiece. Set on an ‘ordinary’ road in an unnamed Manchester suburb, The Street takes as its focus a separate set of characters from one or more of the houses each week. Naturally, certain figures appear across numerous episodes with storylines subtly intersecting. More broadly, the drama has a dual structure enabling its episodes to exist as standalone pieces while rewarding committed viewers with a wider narrative focus; with common themes stretching across the arc of the series. The unique nature of this format tells us much about the success of The Street.

Each episode has its own thematic concerns deeply rooted in the socio-political sphere. Off the top of my head, issues such as age discrimination; racism; immigration; drugs; petty crime and disability, have all been handled with consummate craft as McGovern moves from household to household with each instalment. This engagement with contemporary mores never feels like a lecture or a polemic, as some one-off dramas or mini-series may appear to. Rather, by incorporating the individual topics within a wider narrative system, McGovern exhibits a commercial instinct that ensures a palatable facilitation of his substantial thematic palate. The connections that hold the street – and the series – together provide it with a kind of soap-opera like quality which sees us engaging with the work on two levels: 1) as a serial drama which grips us from week to week and 2) as a set of distinct takes on the social milieu.

This format got me thinking about The Street as a 21st Century ‘Play for Today’. The BBC’s old single drama heritage may no longer be sustainable in a multi-channel dumbed-down age, so McGovern converges the social slant of the tradition with the more immediate and popular generic textures of the soap.

This isn’t the first time such an approach has been adopted successfully, indeed, it would be unfair of me not to mention Paul Abbot’s brilliant Clocking Off which ran from 2000-2003. Like The Street it utilises a large narrative space – in this case a textiles factory – and uses a multi-episode format to focus on a different set of characters in each episode.

The use of these universal signifiers of the everyday – the street; the workplace – invites a reading of their significance in terms of the nation. Setting the action in locations which offer a multiplicity of narrative possibilities in recognisable contexts, allows for a broadness of approach which enables the writer to draw on overarching themes; both social and political, and those of a more subtly humanist tendency; tapping into the connections and disjunctions which define British society. Like the multi-level approach of The Wire, works like The Street dramatise societal institutions to both engage and inform the viewer, deploying cogent narrative strategies alongside an acute awareness of the issues that concern and involve the wider public.

David Forrest

Ken Loach’s Looking for Eric looks set to be one of his most successful films to date. Yes, the star attraction of Eric Cantona will bring hordes of Loach virgins to screens up and down the country, but more than that, its optimism and unqualified comedy make it a highly palatable commercial entity in its own right. I duly found it hilarious and heart-warming in equal measure and I would recommend it, but my enthusiasm is not without some reservations.

Loach has been making didactic, uncompromising and often brutal realist cinema for 40 years, so he’s entitled to something of a departure. Critics have acknowledged that the presence of a star figure (Cantona) and his role as weed-influenced fantasy figure conjured up by the emotionally fragile Mancunian postman Eric (Steve Evets) represents a shift in the naturalist register that has so distinctively marked Loach’s oeuvre. This is a short-sighted observation. Loach is no stranger to subjectivity, flashbacks and explicit internalisations of protagonists can be identified in a wide array of his films: from the figurative treatments of mental illness in In Two Minds and Family Life, to the framing device of Land and Freedom and the tortured memories of his troubled protagonists in Ladybird Ladybird and My Name is Joe. In all the aforementioned (and in Looking for Eric), the use of these devices can be justified on the basis of narrative efficiency – at no point do subjective motifs infringe on the dominance of the central aesthetic or formal template. In Looking for Eric the departure comes from somewhere else, it is the delivery of the socio-political message, so central to Loach’s work, that marks a profound change.

You can be sure of one thing in a Ken Loach film, at numerous points a group of characters will exchange views on a social or political topic and, invariably, the message of the Left is heard with clarity and conviction. Loach uses dialectics to humanise abstract discourses, emblematising his characters to convey a chosen polemic. Looking for Eric is no exception, I think immediately of the scene where the modern, corporate Manchester United, and the supporters-run F.C. United are compared, with the latter ultimately being identified as more virtuous (the gangsters are the ones who can afford to go to Old Trafford, while the postmen watch F.C., moreover in the climactic battle, F.C. United fans storm the villains’ house, covering their possessions in red paint). More subtly Cantona’s mantra delivered to the disaffected, seemingly isolated Eric: “Always trust your team mates” is played out in real terms when the community unite to solve the protagonist’s difficulties (here a more crude dichotomy of individuality versus commonality is evoked in heavy-handed but effective terms).

This marked foregrounding of the social/political position in Loach’s work is usually given a resonance and afterlife beyond the films. For me, this is the one of the greatest strengths of the director’s approach: narratives are left without conclusion and deep uncertainties remain; the issues that the films raise do not disappear when the end credits roll, and the viewer is left in no doubt about that. Compare this approach to the use of socio-poltical issues in Billy Elliot or The Full Monty and we see a clear difference, post-industrial decline is evoked as backdrop and is duly enveloped in heroic denouement.

Significantly, despite Looking for Eric’s socio-political potential; the film’s ending is markedly conclusive; all loose ends are tied up, the quest for Eric’s happiness and fulfilment is completed. Thus we don’t leave the cinema thinking about gang crime; the decline of the family; and the vulgarity of the modern super-club, instead we leave with a smile on our faces because lovely Eric is content again. This isn’t the first time Loach and screenwriter Paul Laverty have opted for a happy ending, in Ae Fond Kiss ‘star-crossed lovers’ Casim and Roisin re-unite. Yet their romance is qualified by corrosive religious sacrifice, as Casim walks away from his Muslim family and Roisin from her Catholic job. Looking for Eric is different because there is no glimmer of human sadness, no sign of the reality beyond the screen. Loach’s films should make you want a conversation; a debate, Looking for Eric just makes you smile.

By David Forrest

In talking about the recent TV adaptation of David Peace’s Red Riding Novels, The Red Riding Trilogy, identifying a shared aesthetic is problematic. While the screenwriter (Tony Grisoni) and source material are the same across these three Channel 4 films, the directors are not; each bringing with them their own unique approach to Peace’s contemporary Gothic vision. However, Julian Jarrold’s (1974), James Marsh’s (1980), and Anand Tucker’s (1983) presentations of the West Riding are marked by a similar sense of abstraction that inverts the paradigmatic imagery of the North.

One of my central interests is the way in which vast external spaces often function in realism as spheres of figurative interpretation, in Red Riding this expansiveness is curtailed to re-deploy the iconography as narrow and foreboding, emblematising the trilogy’s thematic concerns of insidious evil and corruption within its own visual schema.

The village of Fitzwilliam pops up in all three films. I grew up in the next door in Ackworth, and the ‘Fitzy’ of Red Riding is certainly not the one that I know. Even if the producers and directors had chosen to film in the real location, one senses its unbridled ‘otherness’ would still be conspicuous. The only establishing shots are fleeting, and often come in the form of point-of-view perspectives; giving an all-together more condensed view. Narrow rows of houses, drab allotments, and cooling towers barely visible in the distance dominate the diegesis. There is no masterful, all-inclusive vision of the space; instead its elements are presented in fragments – never allowing a sense of locality or familiarity to emerge, while maintaining an ever-increasing atmosphere of horror and inhumanity.

Similarly, the premises of the West Yorkshire Police carry a distinct air of alienation. No long shots, or gentle foregrounding here. Instead, sharp and almost invasive close-ups of brutalist modern architecture consume the frame, the jagged edges and labyrinthine overlaps signifying the tangled passages of cold evil that characterise Peace’s take on the constabulary.

Thus, one of the many interesting elements of Red Riding as a screen text is the manner in which the terrain of the North, so long a central part of realist iconography, is radically subverted to accommodate unfamiliar generic pastures. As the odious Molloy (Warren Clarke) says: “To the North, where we do what we want.”

By David Forrest

On Tuesday night, I stumbled across the BBC’s three-part drama Occupation. I’m not the biggest James Nesbitt fan so my hopes weren’t too high and having watched the final episode last night, I’m now even less of a James Nesbitt fan, even more of a Stephen Graham fan and am filled with pleasant surprised at something substantial on the BBC’s main channel.

Occupation focuses on three friends, Mike (James Nesbitt), Danny (Stephen Graham) and Hibbsy (Warren Brown), who serve together for the British Army in Basra. Having finished their final tour in 2003 each returns home. Mike struggles to re-adjust to family life after falling for an Iraqi doctor, Danny turns to drugs and prostitutes as he refuses to face up to his Alzheimer’s’ ridden mother, and Hibbsy faces an unfulfilling career as a bouncer. Each returns to Iraq: Mike to pursue his lover, Danny to make money as private security contractor, and Hibbsy to work for Danny on an all-together more idealistic quest to re-build the war-torn country. Across the three episodes things get worse for the lads in different ways, culminating in the death of Mike’s young solider son, a tragedy for which all three men are, to varying extents, culpable.

For me, a drama at 9pm on BBC1 signals cheese-ridden, infantile pap. Here was something that was engaging and relatively uncompromising which was based around a divisive and topical range of issues, underscored by a couple of superb performances. Personally, I found the love story over-wrought and unnecessary but I can understand why screenwriter Peter Bowker saw fit to sweeten the otherwise harsh pill of emotional and psychological corrosion that pervades the drama. Indeed, there are very few concessions to the conventions of mainstream TV drama; the film’s conclusion (a stunning scene at Mike’s son’s wake as the three men argue) derives no clear moral message from the three characters’ vastly differing take on the war. Moreover, Occcupation adopts a stark aesthetic which, with its distanced and static compositions, has much more in common with European art cinema than Casuality or Holby City. Occupation offers hope that good, inclusive, and serious drama has a future on Britain’s most popular channel.

I was also moved to think of Occupation as a wartime narrative to be compared to the British war films of the 40s (propaganda/realism) and 50s (reflections on conflict). While such a parallel may seem pretentious, I think it interesting to identify the consistencie in screen culture across the decades of the solider, such a dominant icon of British nationhood. For example, the manner in which Occupation moves between the soldiers’ domestic spheres and their wartime environments recalls the use of flashback in Coward’s and Lean’s In Which we Serve. While the tripartite symbolisation of the inclusive (for propaganda purposes) British class system through In Which we Serve’s three protagonists is absent in Occupation, what we do see is a similar attempt to render the conflicting entities of home and service as a means of intensifying and humanising the portrayal of men at war. Likewise, the way in which Occupation approaches issues of post-war readjustment got me thinking about the wave of British war films in the late 40s and early 50s that dealt with the problems faced by soldiers searching for meaning in peacetime. Basil Dearden’s The Ship that Died of Shame immediately springs to mind, mostly for the similarities between the unscrupulous George (Richard Attenborough [who buys the boat he served in during the war in order to import contraband produce to Britain]) and Danny in Occupation, both of whom face impotent moral derision from their conflicted friends and former superiors, Bill (George Randall) and Mike, respectively.

By David Forrest

When we think of period drama, particularly in the 1980s, it is natural to anticipate a kind of faithful conservatism aligned to a mainstream propagation of national pride and mythology. The all-conquering Chariots of Fire, numerous Merchant Ivory productions, and lavish serials such as Jewel in the Crown can be actively juxtaposed against the more oppositional and socially involved film and TV that emerged in the Thatcher years, creating a polarity of address which seemed to render the divided national mood. ITV’s 1981 adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited can certainly be read in this manner, yet such reductive engagements would fail to comprehend the genuinely challenging nature of the series’ stylistic and formal elements. While on its broadcast Brideshead was hugely popular, and is still talked of as the very paradigm of costume-drama, it is also a work of great complexity that encourages a multitude of understandings.

A recent film adaptation of the novel butchered its source material into a meagre 133 minutes, in contrast the television version extended across 11 episodes spanning 659 minutes. As such, the nuances and subtleties of Waugh’s prose are visible and alive in ITV’s take on the classic. The multiple themes of the source text are allowed to evolve at a gentle and elegant pace; they are rarely at the mercy of the demands of narrative. One episode in which this is particularly significant is the second: “Home and Abroad”. In terms of plot, Charles (Jeremy Irons) goes to stay with Sebastian (Anthony Andrews) at Brideshead during the summer vacation, once there Sebastian decides that the pair should travel to Venice to stay with his estranged father, Lord Marchmain (Laurence Olivier). That is it. Of course, these nuggets of narrative information have relevance for the wider progression of the drama; the episode serves to underline the increasing depth of Charles and Sebastian’s affection for one another and introduces us to Marchmain, a character who holds great relevance to the development of his family as a single entity and as individual characters, and one who serves to encompass many of the novel’s symbolic allusions to both a decaying society and an ever loosening system of beliefs. Despite these aspects, on paper, the episode seems minimal. Yet great substance is summoned by a weighty supplementation of the narrative elements with a persistently conspicuous emphasis on aesthetics.

Visually, the episode is dominated by repeated long-takes of the elegant exteriors and interiors of Brideshead, and later by Marchmain’s home and the many intoxicating aesthetic delights of Venice. I’ve spoken before on the blog about the way in which sustained environmental shots can be seen to signal authorial presence, but here in the realm of adaptation, I think it is possible to ascribe a different meaning for them. Rather than serving to highlight the spaces between the viewer, the author and the image, Brideshead’s painterly aesthetic can be seen to function as a reflection of its narrator, in this case the painter, Charles Ryder. His distanced gaze and a subsequent failure to breach the house’s apparently sublime and transcendental internal life define Charles’ engagement with Brideshead and its inhabitants. As Waugh’s central narrative presence, Charles finds an aural vocabulary to express this fixed position of observation; which equally renders the reader complicit in his unabashed fetishism, yet this key tenet finds new life in the television adaptation. The lingering expositions of intoxicating landscapes and architecture mirror the sensuality of Charles’ surface wonderment at the new world he so passionately embraces, thus, the spectacular image replicates the aesthetic obsessions of the narrator. The image; the surface; the outside, are all that he has – a point made with powerful resonance by this hugely accomplished work.

By David Forrest